Introduction to Transfusion Medicine

Transfusion medicine is a specialized medical field focused on collecting, processing, testing, storing, and transfusing blood and blood components (like red cells, platelets, plasma) for therapeutic uses, ensuring safety and efficacy for patients.

Transfusion medicine is a sub-specialty of clinical pathology and deals with the collection, processing, testing, storage, and administration of blood and blood components. This is what makes this system safe and reliable the moment you enter a blood bank and start working. It is not merely the matter of mere blood transfusion, surgery, trauma care, hematology, oncology, obstetrics, and critical care; the critical coordination of these services is what must be incorporated into patient management. The end result is the safe and effective practice of transfusion through the knowledge of immunohematology, blood group systems, compatibility testing, donor screening, and transfusion reactions.

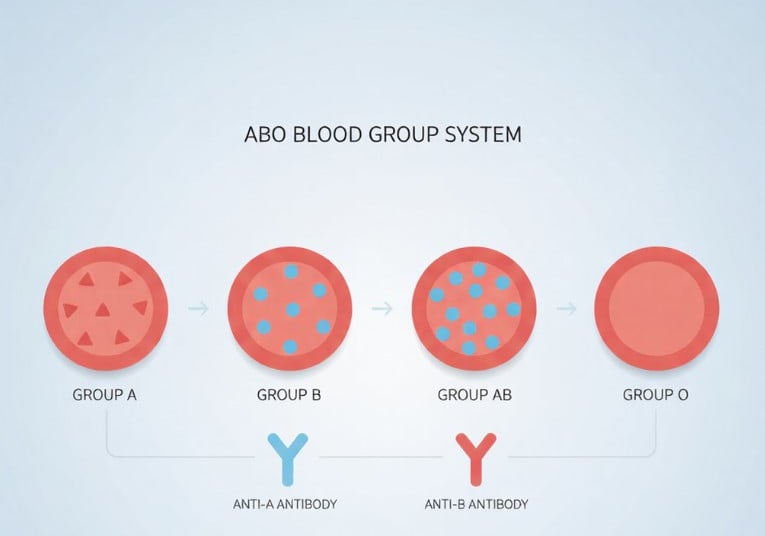

A full knowledge of human blood group systems is an essential basis of transfusion medicine. Being a medical student, you must be aware of genetically determined antigens that exist on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs), since the risk that accompanies mismatches, leading to severe hemolytic transfusion reactions, is potentially fatal. The International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) has identified over 45 blood group systems and over 360 antigens, but few of them are of major clinical importance, and any person in a hospital should be aware of ABO blood group and Rh blood group system.

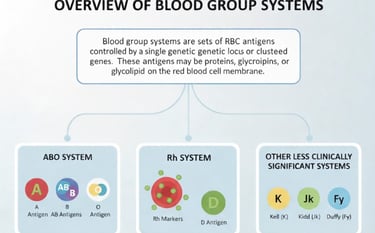

Overview of Blood Group Systems

Blood group systems are defined based on a set of antigens controlled by a single genetic locus or a cluster of closely linked genes. These antigens are typically proteins, glycoproteins, or glycolipids found on the RBC membrane. Among all systems, the ABO and Rh systems are the most important due to their high immunogenicity and widespread clinical implications.